Roger Hennedy 1809 – 76

Roger Hennedy was born in 1809 at Carrickfergus, near Belfast, of Scottish parentage. His family had changed the initial letter of their surname from K to H. This may sound more Irish but it is strange as Kennedy had been quite a common name there since the ‘plantations’ of Lowland Scots to Ulster, initiated in the reign of King James VI.

Roger Hennedy was born in 1809 at Carrickfergus, near Belfast, of Scottish parentage. His family had changed the initial letter of their surname from K to H. This may sound more Irish but it is strange as Kennedy had been quite a common name there since the ‘plantations’ of Lowland Scots to Ulster, initiated in the reign of King James VI.

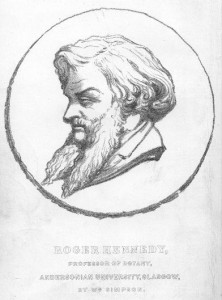

Hennedy followed an unusual career path for a professor of Botany. His life is traced by his friend William ‘Crimea’ Simpson, the famous war artist, in a biographical note published in an ‘In Memoriam’ edition of his Clydesdale Flora (Hennedy, 1878).

From the age of two he lived with his grandfather, who ran a local store, and as he grew up Roger helped him. After his grandfather’s death he became apprenticed as a block cutter to a local calico printer. However, finding his master ‘tyrannical’ he ran away to Scotland where he completed his apprenticeship with a Rutherglen firm of calico printers. In 1832 he left to join the Customs in Liverpool, but finding this uncongenial he soon returned and joined a firm of muslin printers, again as a block cutter.

By this time, however, lithography was replacing the block cutting method of printing in the textile industry and he adapted to the change. He became very skilled at the new process and he designed new patterns, mainly of floral designs, which he then transferred to the stone. His developing skill in drawing led to a closer interest in plants, and in 1838 “owing to a lull in his work, he went to Millport, Isle of Cumbrae and took up the study of Botany merely to pass away the time”. It was here that he also developed a special interest in diatoms, for which he was to become a recognised authority. However, he continued his career as a designer of muslin patterns, working for two other firms before setting himself up with a partner in manufacturing sewed muslins. His botanical interest consumed all his spare time, and in 1848, following the founding of the Athenaeum, he started to teach a small botanical evening class. A year later he also started lecturing at the Mechanics’ Institute.

On 2 July 1851 the Natural History Society of Glasgow was formed by nine “gentlemen interested in the pursuit of natural science” and Roger Hennedy joined them a few days later when John Scouler addressed them and was elected their first Honorary President (Sutcliffe, 2001). Scouler had been a Professor in Dublin since 1834, having previously been Professor of Natural History at Anderson’s University. Hennedy, however, still continued in the muslin trade. According to the Post Office Directories (which are not always reliable) he set up his own business as a sewed muslin manufacturer in Queen Street in 1856 and this continued until 1871.

Meantime in 1863 he was appointed Professor of Botany at the then Andersonian University, a post he held until his death in 1876. William ‘Crimea’ Simpson attended his first classes at the Athenaeum and they became firm friends. They went on excursions together, Hennedy botanising and Simpson sketching. They both got to know Hugh MacDonald, author of Rambles Around Glasgow (MacDonald, 1854), who, like Hennedy, had been apprenticed as a block cutter to a calico printer.

In MacDonald’s book there are references to the two of them, although not by name (vide Simpson, 1903), on an excursion to Robroyston and Chryston, when Simpson was on a return visit to Glasgow. “Our flower-loving friend is now in all his glory poking and prying along the vegetable fringe that skirts the path. Every now and then we are startled by his exclamations of delight, as some specimen of more than ordinary beauty meets his gaze”.

MacDonald stresses the breadth of Hennedy’s natural history interests, and ends in his inimitable melodramatic Victorian style when Hennedy picks up a toad: “Of course, we shrink back in disgust, but that won’t satisfy our philosophical friend who talks contemptuously of ignorant prejudice [and gives] an account of the monster’s habits and mode of living” before letting “the loathsome creature crawl away”. Meanwhile “Our artistic companion … set himself down … to transfer a fac-simile … into his sketch book”. The book includes a copy of the sketch Simpson had made of Cardarrock House on this outing.

Simpson corresponded with both Hennedy and MacDonald from the front during the Crimean War, and Hennedy’s herbarium includes a specimen of a Linum sp. collected on 13 December 1854 from “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” (vide: The Charge of the Light Brigade). Hennedy also became closely associated with Walker Arnott (Regius Professor of Botany, University of Glasgow). They conducted a scientific correspondence for over 20 years and also went on excursions together, Hennedy then especially collecting diatoms. On one occasion they were near a group of colliers who were puzzled by their antics. Hennedy overheard one of them saying of him: “that wee ane’s daft, he’s clean gyte; see, he’s gathering glaur and pittin’d in a bottle”. His interest in diatoms is commemorated in Navicula hennedyi and Toxarium hennedyanum. The eminent phycologist William Henry Harvey named an Australian genus of Rhodophyta (Red Algae) in his name – Hennedya – as well as a species first found off the Isle of Cumbrae – Actinococcus hennedyi, the valid name of which is now said to be Haemescharia hennedyi.

An interest in mosses also brought him a commemorative generic name: Hennediella. This genus is found mainly in North America, but as an alien elsewhere, including the British Isles. It has recently been recognised as a more important genus than originally thought. It is even referred to in A Short History of Nearly Everything (Bryson, 2003) and a revision has been published listing 15 species (Cano, 2008).

Hennedy recounted to Simpson how he collected a large specimen of Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis) one Sunday morning, at a time when the Sabbath was strictly observed. With bad timing he found himself walking through a village as the ‘Established’ Kirk was ‘skailing’ and he passed a long procession of serious faces. To his even greater embarrassment he then passed the Free Kirk as the congregation was coming out and he was mortified when they showed their astonishment at seeing him walking along with his copious plant on such a day! Simpson records that Hennedy was of a rather solitary nature, and spent his time studying alone well into the night. He had little regard for money and often gave his time freely to his students. His wife, Margaret, the daughter of David Cross of Rutherglen, is recorded as: “a lady whose energy and industry in relation to her husband’s work deserves better mention that can possibly be given…” (Simpson in Hennedy, 1878).

The family lived at Grafton Place, close to the College, and the 1861 Census Returns show they have five grown up children living with them. Three girls and one son, William, are recorded as working with their father as “sewed muslin manufacturers”. William appears to have had some botanical interest as the herbarium includes three of the rarer alpines on Ben Lawers and a specimen of the Fortingall Yew collected by him. Their second son, David, a salesman, is recorded in the Post Office Directories from 1869 as D. Hennedy & Co., with the same business address, in Queen Street, as his father. By the 1871 Census, when Roger Hennedy is a Professor of Botany, the other children have left home. Shortly after this they moved to Whitehall, Bothwell and, according to the Post Office records, son David continued to live there until 1891. Roger Hennedy died in 1876 at his home in Bothwell.

Roger Hennedy Grave– Upsilon 144

Roger Hennedy Grave– Upsilon 144

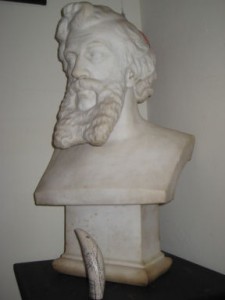

The accompanying sketch of Hennedy is by Simpson, who explained how it was made: “He would never have allowed a portrait of himself to be done. I chanced to be on a visit only a few weeks before his death. … As the family were anxious to have some resemblance of him, I made notes of his face, without his knowledge, … and have been able from them to make something of a likeness”. In 1886 it was “decided a memorial for the late Mr. Hennedy should take the form of a marble bust to be placed in Anderson’s College” (Proc. Nat. Hist. Soc. Glasgow 1886). Although this was done, its present whereabouts is not known. However, Simpson also made an oil painting from the sketch, and this is held in the Collins Gallery.

Hennedy Bust (discovered in Texas, USA)

Hennedy Bust (discovered in Texas, USA)

[Slightly amended version of an account by Eric Curtis in The Glasgow Naturalist Vol 25, part 2 (2009); reproduced with permission. Hennedy’s herbarium is now at Glasgow Museums Resource Centre]

References

Bryson, Bill (2003) A Short History of Nearly Everything. Doubleday, London, New York.

Hennedy, R.(1878, In Memoriam Edition). Clydesdale Flora. David Robertson, Glasgow.

MacDonald, H. (1854, First Edition). Rambles Round Glasgow. James Hedderwick, Glasgow.

The “In Memoriam” edition of Hennedy’s Clydesdale Flora can be viewed or downloaded at http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/64457